April 1st, 2025

Explora Articles The Voros' cone and the futures of HR

March 20, 2023 9 min

When it comes to envisioning the futures for the HR function in an organization, a tool such as the 'futures cone' can help us approach this challenge from new perspectives.

In December 2022, Sandra Durth, Neel Gandhi, Asmus Komm, and Florian Pollner published an article on the McKinsey & Co. website titled “HR’s new operating model,” in which they explained how the “operating model” of the Human Resources function is changing in many companies to provide value in a turbulent environment. Based on interviews with over 100 executives in this function, the authors identified five emerging archetypes of operational models for HR, which were the result of different combinations of eight “innovation shifts”. In addition to an “enriched” model of Dave Ulrich’s classic framework, in which HRBPs play a more active role in process execution, which they call “Ulrich+,” the authors identified an “Agile” model, in which emphasis is placed mainly on speed and quick resource allocation; an “EX-driven” model, in which the focus is on employee experience to win in the talent race; a “Leader-led” model, where the priority is to empower line managers to create “human-centered” interactions; and a “Machine-powered” model, characterized by the intensive use of technological solutions to automate processes and exploit the increasingly large volume of data that organizations have to improve decision-making about their people. The authors concluded that the challenge for professionals in the field is to identify which of these operating models fits best with the specific needs of their organization, bearing in mind that different archetypes may fit better for different units, which may make a combination of several of these operating models the best solution for the organization.

Reading that article reminded me of an Accenture report from 2015 titled “A New Blueprint for HR.” Some of you may remember it. In that document, they discussed how the organizational models of the HR function in companies were evolving from the dominant model at that time, which was based on groupings of internal clients, business partners, centers of excellence, and shared services centers inspired by Ulrich’s thesis (1997). The authors saw that new HR organizational models were emerging in response to the various business challenges faced by companies, whether it be the optimization of operations and costs, the need to align with customer preferences, or the need for agility in a volatile environment. In some companies whose priority was optimizing operations, the authors identified an emerging model they called “Lean HR,” an evolution of Ulrich’s traditional model, in which the HR function decreased in size and was divided into three parts: a shared services unit, a small corporate function composed of highly specialized professionals, and a small number of planning and analysis experts. Other companies focused on their relationships with both internal and external customers and decided to organize their HR function around “talent segments,” so instead of assigning Human Resources Business Partners (HRBPs) to business units, they appointed “talent segment managers” responsible for managing strategic talent categories. And some companies that prioritized agility evolved towards models inspired by the way professional services firms have traditionally been organized, based on teams of internal HR consultants, even with a service charging model in some cases.

However, the Accenture report had a particularity. In addition to those emerging practices, which some pioneering companies were already experimenting with at that time, the authors dared to anticipate some more radical models that technological advances could make possible. For example, if the main goal is to save costs, why not imagine a future where the HR function has disappeared from organizational charts? On the other hand, if the company seeks to ensure the centrality of its customers, both internal and external, we could think of a scenario where digital advances will allow employees to define their talent practices, and HR will be reduced to a small group of professionals who will establish guidelines and take care of maintaining the digital platforms through which people management will be carried out. Whereas, if the priority is the agility of the organization and the quick allocation of resources, the function might evolve towards a “just-in-time” model, based on agile project teams constituted ad hoc to respond to specific needs, composed of a variety of people from the company, such as employees, managers, experts from other functions, and even external customers.

Yet, the most valuable contribution of both documents is that they help us realize that talking about the “future” of the HR function in singular, as a single future, a fixed point on the horizon connected to the present through a straight line, is an excessively reductionist vision that can become dangerous for an organization. Particularly in a highly volatile context.

There can be many futures for HR, and as the Accenture report suggested, as we look up and move away from the present, we discover new possibilities. Many more possibilities than those offered by the two reports I referred to, which, to begin with, are limited to the futures that may be most desired (or at least most convenient) for companies depending on their circumstances; and, of course, many more possibilities than those proclaimed by certain authors or consulting firms that try to convince us that the best future for HR is a specific one.

One of the common problems in the HR function is that we often start building one of these futures because a consultant recommends it to us, because we read it in a report, or because we copy it from another company, without having previously devoted a minimum of time to imagining and evaluating other alternatives. An exercise for which we do not need much time or resources, and for which we can rely on some simple tools that foresight professionals have been using for some time. For example, the so-called “futures cone”.

The futures cone

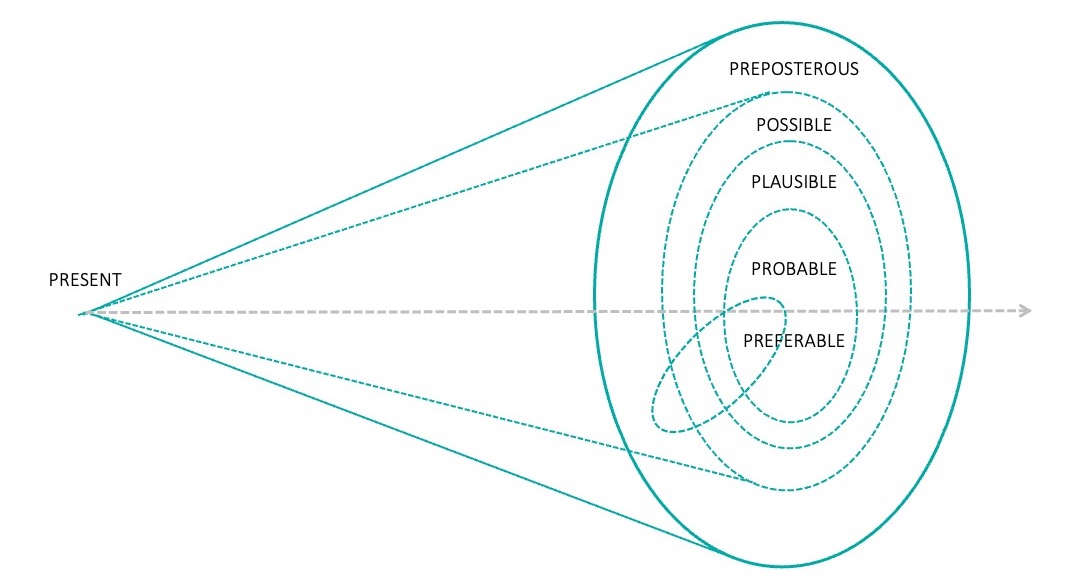

For those of you who are hearing about this tool for the first time, the cone of futures, also known as the “Voros’ cone” for having been popularized by Joseph Voros, a renowned researcher, consultant, and university professor in the field of foresight and futures studies, is a graphical model that helps us broaden our perspective when we think about the future, or rather the futures, of anything. Although, as Voros himself acknowledges in the book Handbook of anticipation: Theoretical and applied aspects of the use of future in decision making, edited by Roberto Poli (2017), he was not the first author to represent the future in the form of a cone. In 1990, Charles Taylor wrote about a “cone of plausibility” that defined a range of plausible futures extended over a time frame, including a “reverse cone” towards the past, and in 1994, Hancock and Bezold used cones to graphically represent Henchey’s (1978) taxonomy of futures.

This model represents the future as a series of cones inserted into each other as if they were ice cream cones on a counter, except in the model they are laid horizontally. Its apex, on the left, represents the present, while its base, on the right, reflects how new possibilities open as we move toward the future. An idea that assumes that the future is indeterminate and “open,” rather than inevitable or “fixed.”

Each of those cones represents a different class of futures.

The outermost and widest one is the cone of preposterous futures. These are the ones that we currently consider ridiculous or impossible, but we should not ignore them for that reason alone. Voros added this cone to his initial design inspired by Arthur C. Clarke’s second law (2000): “The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.”

The next, narrower cone is the cone of possible futures, where we will classify those futures that we think “could” happen, based on some future knowledge that we do not yet possess but that we could possess someday.

And further inside we find the cone of plausible futures, that is, those “admissible” futures that we think “could” happen based on our current understanding of how the world works (physical laws, social processes, etc.).

(Here I want to refer to an essential element of the model: the so-called “wildcards.” These are highly uncertain but high-impact events that can fall into the categories of preposterous, possible, or plausible futures. They can come in the form of technological advances, natural disasters, geopolitical crises, unexpected social movements, and sudden changes in public opinion, and, given their disruptive nature, they can turn a scenario that we previously considered absurd into a probable future and vice versa. That’s why we should keep a close watch on them.)

With this clarification made, if we continue our descent towards the interior of the cone of futures, we will come across the cone of probable futures, even narrower, where we will represent the futures that are most likely to materialize based on current trends, among which we can mention the projected future, resulting from extrapolating the future from the present.

And of course, we cannot forget about the cone of preferable futures. These are scenarios that we consider “should” or “have to” happen, and that can belong to any of the categories of futures previously described. That is, the desired future can be probable, plausible, possible, or even preposterous. The singularity of this category lies in reflecting our aspirations and goals for the future, making it an important tool for strategic planning and decision-making.

So, where is the value of this model?

In my opinion, the great advantage of the cone of futures is that it helps us think differently. One of its most remarkable virtues is that it opens our eyes to the uncertainty of the future. As we move away from the present, more and more paths open toward an ultimately unknown future. In addition, it reveals to us that classifying a future as probable, plausible, possible, or preposterous is only a reflection of what we know at this moment and that many futures that today seem probable could have been considered preposterous a few decades ago. Finally, it reminds us that the future is not predetermined and that our choices in the present can influence the events that unfold in the future. That’s why it’s essential to think about which futures are most desirable and work towards them.

The futures of HR

Now I propose we use the categories of the Voros’ cone to imagine the futures that may await the HR function in the next decade. What do we find?

If we begin with the preposterous futures, we’ll quickly realize that amidst a rapidly expanding landscape of technological innovation, and in a world where we’re increasingly conscious of the multitude of risks we face (risks that are deeply interwoven and interconnected) drawing a clear line between what is possible and impossible is no simple task.

Let’s think, for example, of a scenario in which technological advances make total automation of human work possible and, consequently, the HR function becomes meaningless. Or in another scenario where human workers receive inputs from their employers that condition their behavior through brain implants, while their performance is monitored in real-time. Or a third scenario where populist currents lead to the triumph of totalitarian regimes, and HR departments evolve into a kind of “political police” whose mission is to ensure that the behavior of workers does not deviate from the dictates of the regime. Is it impossible for these scenarios to happen, or are they just highly improbable?

It’s easy to conclude that to overcome the limits of what we currently consider possible, we must think about truly wild scenarios, like an invasion of Earth by an extraterrestrial civilization that turns all humans into their slaves, or a Matrix-like future where a supercomputer traps us in a simulated reality while using our bodies as a source of energy.

But still, visiting the frontier that separates the possible from the impossible will help us think from a more open perspective about the future scenarios that we could classify in the domains of the possible and the plausible. What about a scenario in which technological advances allow the automation of most of the activities that HR functions in companies currently carry out? What about a scenario in which the demand for wage labor ends up being concentrated in a few companies capable of conditioning the rules of the labor market game, while the rest of the population earns a living through odd jobs? What about a scenario in which governments, to avoid the tensions generated by social inequalities, decide to implement a universal basic income system in which all citizens receive income from the State regardless of whether they work or not? Who dares to say that these scenarios are not possible or even plausible?

Anyway, the most interesting debate will arise when we start thinking about the futures we prefer and the futures we consider more probable. This is where things get complicated. On the one hand, many variables can lead to the desired future for the HR function of one organization being different from the most preferable future for another, even if both belong to the same sector. For example, if the two companies follow different business strategies. On the other hand, whether a plausible future for the HR function becomes one of the most probable for a specific company depends on the company’s starting point and available resources, as well as contextual factors such as technological innovations, regulatory frameworks, or the reality of labor markets where the organization competes, but above all, it depends on the preferences, decisions, and particularly the actions of the affected parties. And here is where the mess lies.

Different stakeholders may have divergent visions regarding the desirable future for the HR function. Workers may desire a different future for the HR function than the one desired by HR professionals and neither of them coincides with the preferences of line managers and executives. And let’s not forget about external stakeholders. It may be the case that the customers of the company or the community in which the company operates also have different perspectives…

This is why it is so important for HR professionals to understand that the future of their function in their organizations does not depend solely on their desires, but they need to consider those other stakeholders and assume responsibility for managing the tensions that may exist between their different visions. Especially if they truly aspire to turn that desired future into a probable one and translate it into practice.

***

To shed light on this topic, at Future for Work Institute we have launched a survey to explore the most desirable and probable futures that HR professionals envision for their function in the 2030 horizon. If you are a professional in this field, we encourage you to participate by completing the questionnaire which you can access from this button. It will take approximately five minutes.

***

References

Voros, J. (2017). Big History and anticipation: Using Big History as a framework for global foresight. Handbook of anticipation: Theoretical and applied aspects of the use of future in decision making, 1-40.

***

Image Nathan Winter under a Creative Commons license

Did you like it?

Are you already a user? Log in here